KIMBERLY CHOU'S SUMMER EATING IN TAIPEI

Kimberly Chou is the co-director of the Food Book Fair, an annual event in NYC that celebrates the intersection of food culture, food systems and writing. She is also very fond of grass jelly.

I spent the summer in Taipei studying Mandarin Chinese. It is the place my family comes from and the language I consider my mother tongue. One whose characters, grammar and usage steadily slipped away from me after I dropped out of extracurricular Chinese class in 8th grade. Try telling a 14-year-old girl her Friday nights are best served learning a language with no functional alphabet.

While crawling out of illiteracy these past few months — with four classes a day, five days a week — I also regained the palette I was born with. Pickled, salted twists of vegetables and fermented legumes on hot rice porridge; mysterious, sweet soups and icy desserts with slippery bands of grass jelly, earthy black sesame and green and red and black beans; the urinous but alluring (trust me) smell of boiled bamboo shoots. I loved these flavors once, before I was conscious enough as a small person to make my own decisions of what to eat, or wonder why the go-to family gathering dessert was always, always a stew of hot red adzuki beans when any "American" person (read: not Asian) would choose chocolate cake.

I unlearned these flavors once, but, unconsciously and consciously, I've been getting them back over the last several years. And this summer, my experience in Taiwan revealed itself to be not simply about language immersion, but cultural as well. I deepened my understanding of where I come from in the way that is most immediate to me: through food.

Taiwan is not China. And its food is not — entirely — Chinese. To better understand this small island that has absorbed 500 years of imperialism and influence, mostly from China (many Taiwanese are ethnically Han Chinese, including my family) and Japan, is to consider that its food culture is also freighted with this history. The mixing over time of the foodways of Taiwan's original aborigine peoples, Dutch and Portuguese seafarers, waves of immigrants from different parts of China, Japan and, more recently southeast Asia, has created a distinctly Taiwanese food culture. Questions of Taiwanese-ness — including what constitutes Taiwanese food or who is a Taiwanese person — are ever-changing and continually debated. If there is one thing we can agree on, it's that people on and of this island live to eat.

These are some of the things I ate in Taiwan this summer:

Shao bing (flaky, sesame-studded flatbread that folds like a continental wallet); you tiao (savory crullers) dan bing (egg fried on a thin wheat crepe, rolled up and cut into bite size pieces); dou jiang or freshly made soy milk served sweet and cool by the cup, or salty and hot poured over chopped you tiao, scallions, dried fish and a slurry of sauces — staples of every Taiwanese breakfast stand. One stateside response to my description of the classic starch-on-starch order of shao bing you tiao (the aforesaid bread wallet stuffed with a cruller, often with the addition of an egg fried with scallions): "And people go about their day after eating that?"

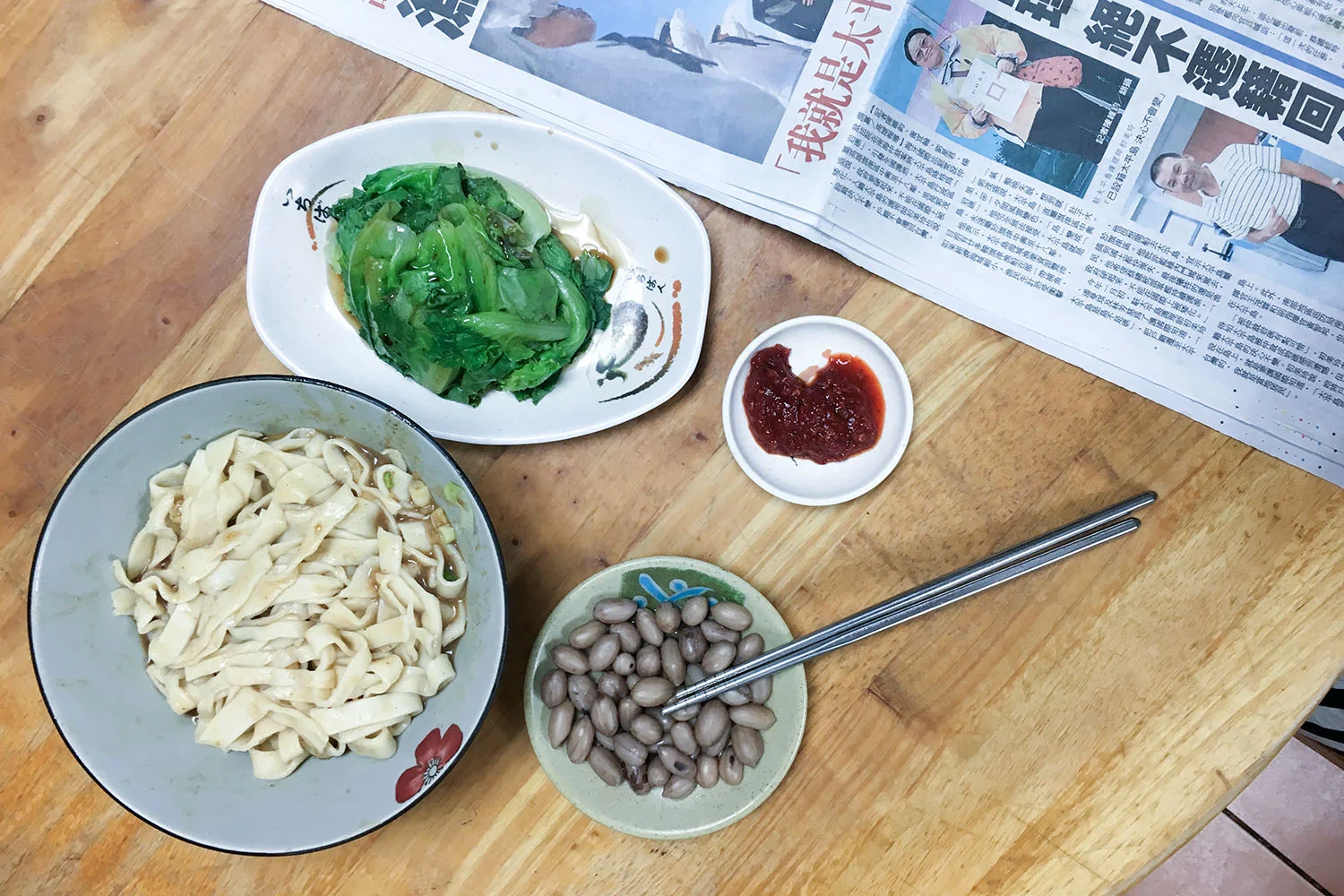

Rechao: A style of eating that I'll try to describe here without making analogous references to "small plates," "Izakaya" or "dive bar." Small dishes of anything that can be stir-fried quickly and cheaply, for $3-5 USD a plate: squid beaks, peanuts with chile, smoked chicken, tofu with salted egg yolks, clams with black bean sauce. Best with a group, best eaten at tables outside while sweating and washing everything down with many tiny glasses of Taiwan beer and unlimited self-serve white rice.

Shaved ice, of the fluffy, milk-based "snow ice" variety topped with fresh mango and condensed milk; as well as pebbly, crushed ice called chhoah-peng in Taiwanese with the more traditional toppings of grass jelly, sweet mung beans, red adzuki beans, barley, etc.

Square, thick white toast with most of the crumb hollowed out and filled with tuna salad, with the cut-out face of the toast magically, surgically retained and buttered and placed back on top.

Chewy, rice-flour and potato-starch based "mochi" of all kinds, including mock-meat versions of the Taiwanese classic "ba wan" of shredded meat and bamboo shoots tucked into a translucent, stretchy skin.

Sachima, a sweet snack made of fried strips of dough or noodles loosely bound together with a brown sugar-molasses syrup and sprinkled with sesame and raisins.

Longan, lychee, mango, kiwi, wax apples, white and pink dragonfruit, white and pink guava, white pineapple, Taiwanese "dirt pineapple," yellow watermelon.

A plate or two of of what one here would be tempted to call "seasonal market greens" at every meal: Sweet-potato greens, lily stems, chayote shoots, mustard greens, cabbages and lettuces and varieties of spinach, steamed or sautéed or cooked in smoking hot woks with lots of garlic. I learned the English names for vegetables whose names I only knew in Chinese or Taiwanese dialect, and the Chinese and Taiwanese names for vegetables I only knew in English. There are some that are much more poetic in Chinese translation: fukuyama lettuce is da lu meior "China girl"; commonly found water spinach is kong xin cai, or hollow-heart vegetable, for its hollow stems.

Tea eggs, hard-boiled eggs stewed in black tea, soy sauce and spices, often found nested a couple dozen at a time in big rice cookers on the counter at your local 7-Eleven; occasionally its bodega sister food, sweet potatoes in their jackets, are on the counter too, my favorite display being sweet potatoes resting on a stack of flat black stones laid in the warming tray, as if they were roasting at a day spa.

–Kimberly Chou

Put A Egg On It #9 features a story by Etang Chen on eating at the night markets in Taipei, you can buy that issue here.